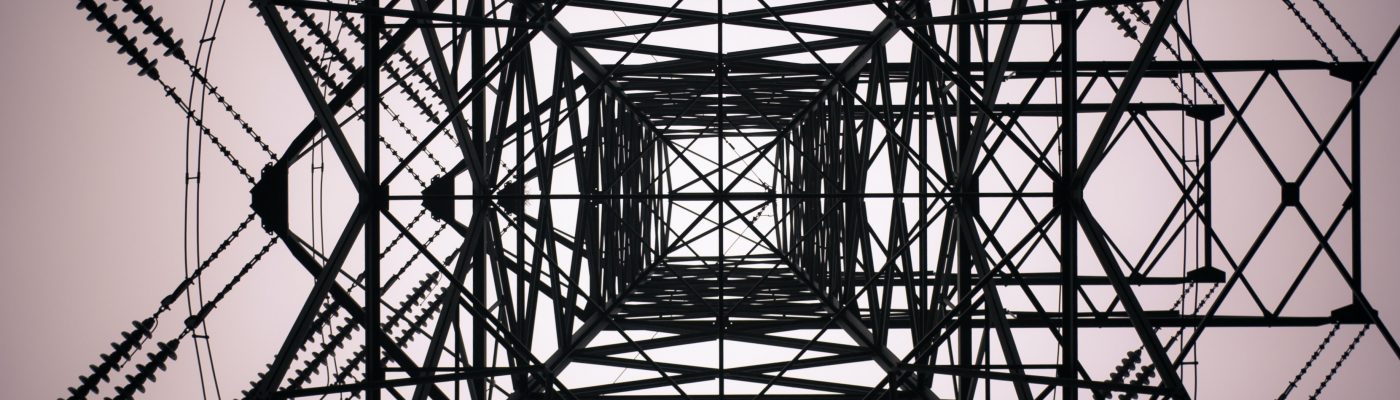

The multiformity of infrastructure

Following the connections between knowledge, technology and practices means approaching infrastructure: the socio-technical assemblages that underpin everyday work. Theorists of Science and Technology Studies (STS) have shown that infrastructure holds the promise to unlock tensions and complexities in the process of knowledge production. As I am thinking more about how to approach infrastructure and incorporate it into my research, I find myself struggling with the identification of infrastructure (Is this infrastructure?). I am currently organizing workshops on Digital Humanities (DH) approaches to the subject of infrastructure and seeking to identify various DH projects as and on infrastructure. It is not straightforward, however, to decide if a particular project is infrastructure or can operate as infrastructure. Besides, I am coordinating the category of Digital Humanities in the extensive bibliography of the Critical Infrastructure Studies initiative that aims to gather resources on the topic of infrastructure across various contexts and disciplines. As road and pipes are easily identified as the examples of infrastructure, it is difficult to define and conceptualise digital objects as infrastructure. It can also be challenging to categorize scholarly resources due to the topic related to infrastructure. The CIStudies.org offers a rich taxonomy and develops into a great database on infrastructure studies across fields.

The more I delve into the study of infrastructure, however, the more I am struggling with its definition. This is a creative paradox that shows how infrastructure as the concept is complex, multifaced and open for contestation. In this post, I want to reflect on the multiformity of infrastructure that makes infrastructure a powerful and engaging object with the embedded power to form and re-form social, cultural, and intellectual configurations.

Our everyday social life and work practices are enmeshed in robust networks of people, institutions, organisations, technical systems, and materials. We rarely think about the conditions and substrates of our practices and engagement in things we care about. Theories of infrastructure studies have thought us that infrastructures are hidden in the background and unnoticeable in daily practices. As a user of well-working infrastructure, you will not notice it unless it is broken and disclosed. The heterogeneous nature of infrastructure makes it also invisible as it is often limited to material things, such as servers and laboratories. But as exemplified by STS work, infrastructure is not a fixed, neutral, and only material construction but rather a complex and dynamic socio-material thing. Bowker et al. showed that the information infrastructure is a distribution of elements along technical–social and global–local axes: “The key question is not whether a problem is a ‘social’ problem or a ‘technical’ one. That is putting it the wrong way around. The question is whether we choose, for any given problem, a primarily social or a technical solution, or some combination. It is the distribution of solutions that is of concern as the object of study and as a series of elements that support infrastructure in different ways at different moments” (Bowker et al., 2010, p. 102). Infrastructure is made up of social and technical components – community and platforms – and their interrelations disclose divergences and disagreements between them. The quality of infrastructure is built by making connections, enabling participation, and facilitating practices. These values prompt the question of social side of infrastructure that discloses hidden interrelations between the system and society, such as who is connected, who is enabled to participate, and whose practices are facilitated. Infrastructure reveals a set of disturbing questions of inclusion/exclusion, connection/disconnection, and scaling up/down in the social configurations. The mechanism of engineering infrastructure has become synonymous with the process of engineering society and culture.

At this point, I want to briefly present four cases when infrastructure has been exposed by the community that challenged its architecture and values.

In the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, government science advisors from twelve countries released an open letter calling on scientific publishers to make all research related to the coronavirus and COVID-19 freely available in both human and machine-readable formats (Call for Open Access to COVID-19 Publications, 2020). As a result, numerous big publisher houses, including Elsevier, Wiley, and Springer Nature gave full access to their content on the COVID-19 for the time of the pandemic situation. Along with this movement, many other academic publishers, knowledge resources providers, and digital platforms and libraries announced the temporary free access to their services and datasets (e.g., VitalSource, Coursera, Cengage, Scholastic). This has ensured that students learning and studying remotely from home have had free access to textbooks and other resources. Another interesting case study constitutes the non-profit Internet Archive that announced the National Emergency Library on 24 March 2020 – a temporary state of getting access to a digital collection of 1.4 million books to ensure that students who “cannot physically access their local libraries because of closure or self-quarantine can continue to read and thrive during this time of crisis, keeping themselves and others safe” (Freeland, 2020). The gesture of the National Emergency Library as charitable as it was, it sparked a heated debate about its legality, which led it to sue the Internet Archive over free access to books by Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Hachette and Wiley (Harris, 2020). The National Emergency Library ended on 10 June 2020 and the library returned to traditional controlled digital lending.

As a response to the pandemic crisis, the academic and cultural entities have set up provisional open infrastructures to facilitate the urgent global need for free access to relevant scientific and literary resources. This has revealed a new analytical dimension of infrastructure that is temporality. It prompts us to think about the temporariness of experience of infrastructure for a limited period and new practices of acting formed upon the temporarily constructed technical systems. It also raises a set of new questions: What will happen with work built upon a temporary infrastructure? At which point will we decide that the worldwide open access to knowledge resources is no longer needed? Who will lose access overnight? How can we sustain a system of open and equal access to knowledge for all not only at the time of global emergency?

The other two examples are related to social infrastructures that include networks and organisations. On 18 July 2020, the Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations (ADHO) released official “Statement on Black Lives Matter, Structural Racism, and Establishment Violence” as a response to social unrest across the US. ADHO is an umbrella organization that coordinates the activities of several regional digital humanities institutions and aims to support the development of local digital research and teaching practices. It has gradually expanded its membership to DH associations established in different parts of the world, including Digital Humanities Association of Southern Africa (DHASA), Japanese Association for Digital Humanities (JADH), and Red de Humanidades Digitales (RedHD). ADHO has become the main digital humanities academic infrastructure with a set of initiatives, aiming to strengthen the field, connect communities across the world, and support the cultural diversity of the field. As ADHO does not take formal positions on political situations in individual countries, this statement was an exceptional event. In light of social concerns, the core infrastructure of the DH community cannot stay silent but must take actions to ensure that its architecture reflects anti-racist and non-discriminatory ethics and combat the inequalities and all forms of discrimination.

In the face of Covid-19 outbreak that revealed long-standing and deep structural inequities running along demographic, geopolitical, and infrastructural fault lines (Fisher and Bubola, 2020; Ogbunu, 2020), the group of researchers established COVID Black – a data organization that aims to help healthcare systems, academic institutions, non-profit organizations, and companies in solving problems around racism and health with data and information services. The interdisciplinary team of experts produce “health data stories” aiming to fight for health equity and end racial health disparities that impact Black diasporic communities and other people of color. This initiative puts Digital Humanities in a dialogue with Black Studies, Medical Humanities and Public Health and provide the infrastructural affordances for social interrogations through collecting and curating Black health data, creating learning solutions for addressing health disparities, and archiving and mapping Black health experiences.

The above cases explicitly reveal the social angle of infrastructure: the network endpoints and social exclusion, the temporality and social disconnection, organisational management, and social justice. This makes me to think more about the relationship between infrastructure, society and culture – the connections well investigated in anthropology and STS, but still not enough discussed in the field of DH. Digital humanities are well positioned to answer these questions by engaging in conceptualising, interrogating, and making infrastructural components. Digital humanities artifacts are co-produced by human, technical systems and operational methods that contribute to delivering new models for acquiring and producing knowledge. Digital outputs – digital platforms, tools, collections, archives, and databases – constitute new forms of cultural expression and become the objects of critical inquiry. In recent years, the field has developed into a focal point for critical interrogation of the dominant information system and for the design of alternative social configurations and epistemologies. The growing calls for infrastructural criticism (Liu 2018), transparency (Noble 2018), explainability (Berry 2019), ethical production (Smithies 2017), data decolonisation (Ricaurte 2019) and critical modelling (Bode 2020), stimulate critical reflections on the question of how digital humanists together with research software engineers can contribute to building the world in favor of social justice, safety, and transparency.

The analysis of infrastructure and digital humanities requires a broad way of thinking of infrastructure. This is the conceptual umbrella that includes different types of infrastructure: physical, digital, technical, cultural, social, and methodological. The term “infrastructure” brings to mind HathiTrust Digital Library, the Humanities Commons, HASTAC, FemTechNet, Women Writers Online, Canadian Writing Research Collaboratory, Digital Research Infrastructure for the Arts and Humanities (DARIAH), Humanities Networked Infrastructure (HuNI), Europeana Research Cloud, Figshare, Zotero, TEI, Application Programming Interface, Zooniverse, Scalar, Voyant, Manifold, and so on. What I am interested in, however, is to explore how DH create components of the infrastructural system and how these individual digital objects can be theorized and perceived as the articulation of infrastructure. Scholars across different fields (e.g., STS, media studies and cultural studies) increasingly regard infrastructure as a substrate – defined by Star and Ruhleder as “something upon which something else ‘runs’ or ‘operates’, such as a system of railroad tracks upon which rail cars run” (Star and Ruhleder; 1996). We can see library as a research infrastructure that enables access to resources or servers as technical infrastructure that enables data storage. But what about digital archives and collections that upon which practices are ‘run’ and knowledge is built?

This makes me reflect on digital humanities outputs and the way they can be theorized as the articulation of infrastructure and as the objects engaged in the subject of infrastructure. How can DH become more engaged in social justice through the practices of designing and building tools and archives? How can DH provoke changes through building counter-infrastructures? How can DH seek the infrastructuring of supressed voices through creating digital collections of hidden stories?

I find the concept of infrastructuring used in STS useful since it refers to the process of creating, implementing, and using infrastructure, as well as to the collective practices of these actions. Infrastructuring is an analytical concept that shifts attention from structure to process and has been applied in a few different research communities, including media and design fields (Karasti, 2014; Karasti and Blomberg, 2018). The above questions and the concept of infrastructuring help me to look at digital objects as socio-technical components that contribute to the infrastructuring of social system by connecting excluded communities and by representing data hidden at the bottom of public documents. DH have been critically engaged in the subject of infrastructure in the context of building knowledge resources (digital archives, collections and databases) devoted to histories of minorities (The Colored Conventions Project, Black Press Research Collective, The Cork LGBT Archive), documenting indigenous languages and communities (Ticha, The Real Face of White Australia), building alternative scholarly networks (Global Outlook::Digital Humanities, FemTechNet, Knowmetrics Network), engaging in counter-mapping environmental areas (Calha Norte Portal), and uncovering algorithmic bias (Femicides in Mexico). These projects are not infrastructures per se (or rather not the common image of infrastructure) but the objects that critically question the configuration of public infrastructures: archives, data, and information systems.

Therefore, I see DH as a field well-positioned to interrogate the architecture of infrastructures (as exemplified by the cases of Internet Archive, ADHO, COVID Black), build infrastructures (the examples of HuNI, Women Writers Online, Manifold), and question public infrastructures (the above DH projects revealing the entanglement of public infrastructures with the issues of social justice, social invisibility and data bias).

The growing body of literature on the concept of infrastructure prompts the questions of why the concept of infrastructure is essential for following people’s practices, what kinds of subjects and values are embedded in the infrastructural system, and how infrastructure can reconfigure the power dynamics. These inquiries have been central for STS scholars who have sought to show that the concept of infrastructure is a productive analytical concept that reveals the way the contemporary world is built, connected and represented. STS scholars have seen infrastructure as a relational thing that can help to disclose tensions and divergences present in social life. Attending infrastructure and thinking through infrastructure can help to interrogate and theorize key social and anthropological questions about power, justice, affect, imagination, temporality, materiality, and labor.

In the introduction to the companion “Infrastructures and Social Complexity”, Penny Harvey, Casper Bruun Jensen and Atsuro Morita note that the definition of infrastructures remains elusive given the transformation and emergence of their new forms (2016). Drawing on the aspect of relationality of infrastructure, the authors argue that even minimal characterisation of infrastructure does not allow us to “predict how people will apprehend and identify infrastructures as relevant in their lives, or even what they will see as infrastructural” (2016, p. 5). They propose to approach infrastructures as dynamic and emergent forms which contours cannot be specified in advance. “The fact that infrastructure is a divergent phenomenon does not need to lead to mutual indifference among differently invested actors. To the contrary, as we see it, one of the most exciting things about the current STS and anthropological interest in infrastructure is that it draws into unfolding conversations an increasingly varied array of infrastructural actors materials, offering an ever-expanding range of resources for thinking and acting. In our estimation, these lateral movements are crucial for coming to terms with infrastructure as concept and practice in continuous variation” (2016, p. 6).

Infrastructure displays itself as paradoxical object that is both fixed and dynamic, material and conceptual, inclusive and exclusive. This creative paradox as an intrinsic value of infrastructure makes it the thing of constant contestation and reconfiguration. Its multiformity and heterogenous ways of engagement in its components and articulation lead to embracing diverse conceptual possibilities to reveal the complex relationships between society, culture, data, and technologies. All of this makes infrastructure an exciting object of inquiry.

References

ADHO, 2020, ADHO Statement on Black Lives Matter, Structural Racism, and Establishment Violence, adho.org, July 18, 2020. https://adho.org/blm-structuralracism-establishmentviolence

Berry, D. M. 2019, The Explainability Turn. Stunlaw, December 17, 2019. http://stunlaw.blogspot.com/2020/01/the-explainability-turn.html

Bode, K. 2020, Why You Can’t Model Away Bias. Modern Language Quarterly, 81(1) (2020): 95–124. https://doi.org/10.1215/00267929-7933102

Bowker, G. C., Baker, K., Miller, F. and Ribes, D. 2010, Toward Information Infrastructure Studies: Ways of Knowing in a Networked Environment. In J. Hunsinger et al. (eds) International Handbook of Internet Research, Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 97–117.

Call for Open Access to COVID-19 Publications 2020, Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, March 13, 2020. https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/063.nsf/eng/h_98016.html

Fisher, M. and Bubola, E. 2020, As Coronavirus Deepens Inequality, Inequality Worsens Its Spread. The New York Times, March 15, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/15/world/europe/coronavirus-inequality.html

Freeland, Ch. 2020, Announcing a National Emergency Library to Provide Digitized Books to Students and the Public, Internet Archive Blogs, March 24, 2020. http://blog.archive.org/2020/03/24/announcing-a-national-emergency-library-to-provide-digitized-books-to-students-and-the-public/

Harris, E. A. 2020, Publishers Sue Internet Archive Over Free E-Books, The New York Times, June 1, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/01/books/internet-archive-emergency-library-coronavirus.html

Harvey, P., Jensen, C. and Morita A. 2017, Infrastructures and Social Complexity: A Companion. London: Routledge.

Karasti, H. 2014, Infrastructuring in Participatory Design. In: Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference: Research Papers, vol. 1. New York: ACM Press, pp. 141–150.

Karasti, H. and Blomberg, J. 2018, Studying infrastructuring ethnographically. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 27(2): 233-265.

Liu, A. 2018, Toward Critical infrastructure Studies. NASSR, April 21, 2018. https://cistudies.org/wp-content/uploads/Toward-Critical-Infrastructure-Studies.pdf

Noble, S. U. 2018, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New. York: New York University Press.

Ogbunu, C. B. 2020, How Social Distancing Became Social Justice. Wired, March 18, 2020. https://www.wired.com/story/opinion-how-social-distancing-became-social-justice/

Ricaurte P. 2019, Data Epistemologies, The Coloniality of Power, and Resistance. Television & New Media, 20(4): 350-365.

Smithies, J. 2017, The Digital Humanities and the Digital Modern. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Star, S. L. and Ruhleder K. 1996, Steps toward an ecology of infrastructure: Design and access for large information spaces, Information Systems Research, 7 (1996): 111-34.